Escaping the Cargo Cult: Exchanging blind faith for real-world outcomes

In his February 2024 blog post, Technology is the Problem, Palantir CTO Shyam Sankar presents a compelling argument: the stagnation in growth and progress over recent decades is largely attributable to a misalignment at every stage of the B2B SaaS value chain. Engineering, procurement, implementation, and operations are all fundamentally out of sync with organizations’ true needs.

Instead of focusing on advancing these needs in meaningful and measurable ways, both internal teams and external parties are focusing on other, often self-referential metrics instead. This shift has led to a form of performative progress — a “cargo cult” — with predictably poor outcomes.

The Forces Behind Misalignment

Software companies prioritize technology over client goals, comfortably ensconced in their offices while outsourcing the hard work of client-side implementation.

Procurement professionals create multi-dimensional evaluation frameworks, scoring them with scant attention to actual outcomes.

Consultants develop generalized implementation playbooks, judged more on process methodologies than real-world impact.

Internal IT teams view software through the lens of their preferred activities and team size.

Financial analysts focus on standard, easily accessible, and communicable KPIs.

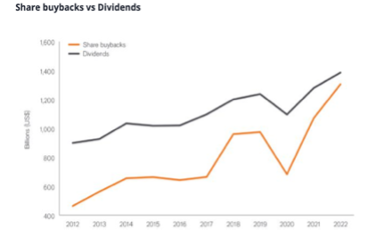

From merger and acquisition activity and share buybacks to climate and DEI initiatives, management focuses on orthogonal metrics that are easier to control than core targets, especially in the short-term.

There is a common thread: self-referential processes that prioritize internal rules and procedures over true progress against core mission.

Should we be shocked? If given the choice, many people will gravitate towards tasks that are easier for them to achieve, more likely recognized to be successful and beneficial to their interests. Absent a forcing function, it would be surprising if anyone acted differently.

Obviously, this is not just a private sector problem.

In his New York Times column “The Problem with Everything-Bagel Liberalism,” Ezra Klein describes how processes that force every major project to serve multiple goals means more often than not, nothing is achieved at all.

“You might assume that when faced with a problem of overriding public importance, government would use its awesome might to sweep away the obstacles that stand in its way. But too often, it does the opposite. It adds goals — many of them laudable — and in doing so, adds obstacles, expenses and delays … [so] that it ends up failing to accomplish anything at all.”

Klein argues that if we really care about outcomes, we need to actually focus on achieving them and not just indulge in the theater of effort.

“And if you think failure really is an option — that it’s maybe even the likeliest outcome — then that demands an intensity of focus… There is a danger… that politics becomes an aesthetic rather than a program.”

We must confront the real question: why is nobody forcing this intensity of focus? Why are those accountable for ensuring tangible progress not insisting that all this activity, time, and resource be devoted, first and foremost, to fulfilling the organization’s core mission?

In other words, why doesn’t anybody scream bloody murder about the cascade of unaccountability and misalignment, and about the lack of delivery?

One possibility is over-confidence. Surely, the next big data-lake/ERP project will be the silver bullet that finally puts all the necessary information in the hands of operators. Then they’ll be able to proactively adjust supply chains, identify manufacturing quality issues before they impact customers, deliver complex projects on time, and optimize hospital schedules so that our patients are home sooner. Surely?!

For this silver bullet scenario to be true, people in all sorts of organizations, public and private, would have to individually and collectively decide that their core operational problems are so trivial — and the chances of them being solved such a given — that it makes sense to layer on additional success criteria and be held accountable for those.

If this happened occasionally, it might be plausible that individuals would allow over-confidence to sweep them into negligence, but this state of affairs is so pervasive and the exceptions to it so rare that it’s likely the true answer is different — and worse.

In order to really “own” an outcome, to drive hard towards it and agree to be accountable for it, individuals have to believe that success, however unlikely, is at least possible. But for most, the lived experience of working with enterprise technology in the last decades has led to complete disillusionment. People have lost confidence it can deliver the things that really matter. Instead, they shift the goal posts, find other metrics to point to, and declare victory.

The Normalization of Failure

How did we arrive at a point where failure has been so systemically normalized that things not working is how the world works?

Let’s look at the operational reality of pretty much every organization (with the possible exception of tech-first companies). For the last two decades, Palantir has been operating at this frontline, and we have consistently been surprised by the fact that no matter how unique the customer and whatever their tech strategy, the same existential problems exist everywhere:

- Siloed transactional systems are optimized around individual process-steps, not end-to-end delivery.

- There’s a lack of a common ontology (i.e., each system models its world differently from every other system — so every definition of apples and oranges is different).

- It’s next to impossible to get a global operating picture — technically systems don’t talk to each other and even if they did, it’s the Tower of Babel.

- Because core transactional systems are rarely replaced (however ancient and creaky they are), the worlds of actions and analytics too often remain decoupled even for the organization that succeeds in creating an enterprise-wide analytical layer.

There are technical solutions to all of this, and Palantir has been addressing these issues step by step. It’s how we ended up as a platform company. However, these remain very hard problems for our institutions, and the (non)-results speak for themselves.

Real-world examples abound, illustrating the consequences of misaligned and outdated IT systems. Take British Airways in 2017: a massive IT system failure led to the cancellation of flights and delays for thousands of passengers during a busy holiday weekend. The culprit? A power surge followed by an unsuccessful systems reboot: an event that any modern, international airline should be prepared to withstand. But their complex and antiquated IT infrastructure rendered them incapable of swiftly pinpointing and rectifying the problem, resulting in significant financial losses and a reputation nightmare.

These incidents are not isolated to the private sector — far from it. “Over budget, over time and under benefit” is sadly the norm across public building projects. Whether it’s at the Holland Tunnel in New York, the BART system in San Francisco, the Channel Tunnel between the UK and France or Berlin’s new Brandenburg airport — regardless of geography, we see the same pattern: years of delay and billions in cost over-runs. And the same is true for building projects in the digital realm with HealthCare.gov as just one ignominious example to stand in for so many like it.

These examples underscore a broader trend of failure normalization, where the systemic inadequacies of enterprise technology are not only expected but accepted as the status quo.

The Severed Transmission Belt and the Fogged Windscreen: How does Enterprise Tech do so little good but so much harm?

The way our organizations have digitized and digitalized was by automating whatever could be automated. The guiding principle was to remove humans from processes wherever possible in the name of efficiency.

The obvious place to start was transactional systems (e.g., an insurance company’s claims processing system). These systems were the first to be re-built from the ground up, disassembling the end-to-end delivery of enterprise outcomes into two categories: those that could be automated and those that could not.

Newly automated process steps could be scaled massively in comparison to what had been possible before, allowing organizations to build up operations around them. So, of course, this pattern was repeated for every transactional system in the enterprise, such that every new system was designed to optimize for its specific process step.

However, these efficiency gains masked a new emerging set of significant vulnerabilities.

As the philosophy was to minimize human involvement, systems were not designed to facilitate a granular, timely understanding of what was happening at each step, let alone an end-to-end perspective.

In essence, systems handling core transactions in the enterprise were removed from the organization’s OODA loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act), and were built to optimize their specific process with little consideration for the wider, end-to-end landscape of operations. Each one was designed and implemented in isolation, with its own language and logic.

While organizations became more efficient at processing transactions and grew accordingly, they also became more vulnerable to system failure. The resulting fragmented systems landscape severely hindered their ability to act cohesively, and the separation of transactional and analytical processes significantly reduced visibility into operations.

By scaling their increasingly complex structures in isolation, organizations failed to recognize they had also cut their transmission belt in several places, and that the windscreen was steadily fogging up.

From the outside, things may appear stable. But the reality is that these organizations are brittle, buckling under the weight of their own complexity.

When crisis strikes — or opportunity arises — whenever something other than “business-as-usual” responses are needed, leadership at all levels find they are grappling with a broken steering wheel and partial visibility at best.

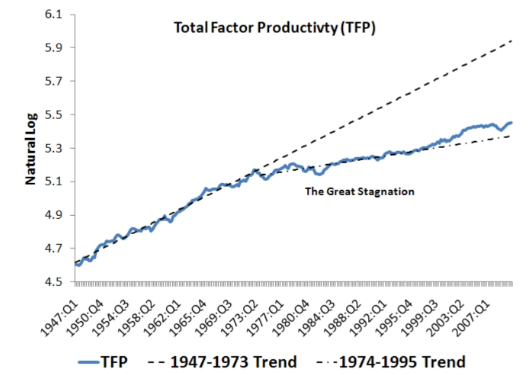

The extent of missed individual opportunities is challenging to discern from the outside — although middling aggregate growth numbers provide a clue. However, crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced many to return to paper and Excel, unequivocally demonstrated how much enterprise technology remains lacking.

The Systemic Issue

One important reason why this is all so hard to fix is that it’s systemic. It’s systemic to the way IT has been deployed at all organizations across the board in the past couples of decades. Few people have ever seen it done differently.

If nobody knows better, there is minimal pressure to change. Over time, the reality of being unable to do things or understand ground truths about an organization’s operations simply gets normalized.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the operating environment for businesses had been relatively stable for a long time, helping to conceal some of the dysfunction. When a company carefully crafts its public image to be one of relentless digital transformation at the very edge of technological progress, nobody wants to admit their organization, much less their team, and even less themself as an individual, might struggle with what most people would think of as “the basics.”

Where is Silicon Valley?

In the early 2000s, every genius in Silicon Valley — except Peter Thiel — was certain of two things: 1) B2B software was a terrible idea due to an annoying sales process, and 2) selling software to government customers was an even worse idea since they would be even more troublesome and had no budget.

So these B2B software companies never came to be, and the best and the brightest engineers found employment elsewhere, mainly at consumer Internet companies.

Palantir swam against the tide not only with B2B software and government clients, but also with the “tip-of-the-spear,” mission-critical use cases for which no other Valley company was building technology. Most challenging, the organizations that needed this technology were not set up to receive it functionally or psychologically.

Yet we persevered, consistently showing up at the operational frontline. It’s in this space we found intensity of focus, and it shaped everything Palantir is and does. Our engineers developed the muscle of testing everything they built against the operators’ core mission. No matter how cool the tech, if it didn’t help the users achieve their objective better, it was discarded. Of course, it’s impossible to know if your software helps your users if you are sitting in Palo Alto. So, our engineers found themselves spending their days — and often nights — in windowless rooms in government buildings or in even less hospitable places. The “forward-deployed engineer” was born.

We hired the best software engineers in the world, ejected them from the comfort of a Palo Alto office, and dropped them in remote locations to spend their days in the service of incredibly skilled but non-technical operators. Everyone on the outside thought this would fail. Alex Karp often said that only something as sexy as James Bond could convince the best engineers in the world to spend their time on something as boring as data integration. Under the surface of that quip is the key to Palantir’s culture and success: we did not look for the sexy problem but for the important problem, and we found the people to whom the important problem is sexy. In the process, we beat out much better resourced companies in the race for the best talent.

This mission remains critical. Our society depends on functioning institutions, and those institutions depend in large part on functioning software. But the software provided to operators is terrible. It’s way worse than anything we take for granted in the consumer space. And the people in Silicon Valley most qualified to address this challenge have not even been trying to solve it.

The Next Shift: After capital allocation must come mindset

Of course, the tide turned in Silicon Valley, and B2B SaaS didn’t just become an investable category — it absolutely dominated where Venture Capital dollars went.

But the shift in capital allocation was accompanied by a mindset of “tech-first” rather than “mission-first.” The tech-first paradigm proved too natural, the hands-off approach too alluring, and the pair too mutually reinforcing for the resulting software to move the needle. When this whole paradigm is enforced by the “Masters of Capital,” as Shyam points out, you can see why the misalignment is so systemic.

What’s evident is that “more of the same” will not get us to a different outcome. If we focus only on the technology and not on the problems that need solving, those problems will not get solved.

Ironically, it is because we expect too much from it that technology delivers so little. We have made it a cargo cult in which we pray that each new technology finally delivers us from the sins of its predecessor.

Organizations and individuals alike need a mindset shift away from the fantasy that technology itself will magically solve our problems. For now at least, it is humans who are responsible for the solutions, and we need the tools and intense focus to do it.

Generative AI has the potential to unlock massive efficiencies in the enterprise and be enormously empowering for employees. But without a systematic change in approach, it will have the same amount of impact as any number of the powerful and much hyped technologies like data science, IoT, and machine learning, that came before it. Namely, next to none.

We must solve these problems and not squander the potential of another technology. The cost of doing so is too high.

Zero growth is an emergency, but the deepening malaise in our societies as nothing seems to quite work is even worse. Many assume getting basic systems to work is easy, or at the very least, possible. If these systems get progressively worse, the obvious conclusion is that leadership is either inept, corrupt or both — and the unity of purpose and confidence we need to move society forward gets ever more eroded.

The truth is much more banal. A blind trust in technology has led us to permit the removal of accountability for outcomes at every step of the process. By expecting technology to deliver too much, we have had to settle for it delivering hardly anything at all.

The path forward demands a collective radical realignment with purpose. It is time to dismantle the cargo cult mentality and embrace accountability to tangible outcomes.

Author

Meline von Brentano, Head of Digital Transformation Strategy, Palantir

Escaping the Cargo Cult was originally published in Palantir Blog on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.